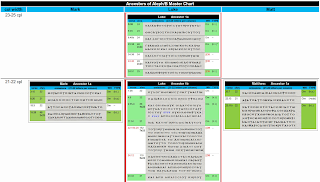

The following chart-pieces can be clicked on to enlarge, and you can navigate back using the back-button in your browser.

Luke (20 - 25 chars per line)

It appears that Luke took a uniquely bad beating during the earliest copying phase, when wider columns were popular. These omissions were not so much the result of bad copying (all copyists make these errors), but rather a result of little or no systematic proof-reading techniques, and lack of experience with the kind of errors most commonly found. This discovery is not particularly surprising, given that Luke would be most popular among Gentile converts and Jews of the Diaspora, where professional scribal technique would be lacking, and a learning-curve would be in operation.

Matthew and Mark have only suffered half as many losses in this period, probably due to the greater experience and care Jewish-Christian copyists were able to exert on the task.

Matthew (17-19 chars per line)

Next, in an intermediate period, while the Gospels were still being copied independently in double or triple columns, Matthew now takes a savage beating from the same loose environment lacking adequate error-correction techniques. The others suffer moderate losses at the hands of different copyists. All of this could have been accomplished in a single manuscript in which either different sources were used for each gospel, or different scribes copied the sections.

Mark and Luke (14-16 cpl)

Mark now gets hit hard in this later period, involving MSS with 3 to 4 columns per page. Luke also suffers significant damage at this time, probably early in the 3rd century. Matthew, probably due to better error-checking, suffers only moderate damage during the same phase. These differences must now be traced to either individual scribes or correctors responsible for each gospel, since they will now most likely be bound together in single books containing all four gospels.

Mark (11 -13 chars per line)

Mark now takes one last pounding, at the hands of some scribe or lazy corrector, while being copied from a MS having 4 columns per page, like Codex Sinaiticus. Luke's Gospel also takes significant collateral damage in this line of transmission.

It may be significant that these two gospels are usually physically adjacent and in the middle of the book, in copies of the four gospels. One can picture a corner-cutting corrector or scribe only proof-reading the first part of the book (Matthew) and possibly the last (John), so that an overseer might be fooled into believing the entire MS has been properly corrected.

Finally, minor omissions of unknown date and circumstance also accumulate in the gospels, on a smaller scale.

The picture is interesting, but tells a sad story, in which Gospels like Luke and Matthew, immensely popular once they were published, took an early beating at the hands of inexperienced scribes using inadequate error-correction techniques.

Conversely, and perhaps more importantly, the damage that Mark suffered seems to have mostly occurred in the later period of multiple-column manuscripts.

It seems that someone in Caesarea, or perhaps Alexandria, mistakenly took an older copy of Mark for a more accurate text. But this text was already badly mutilated from its own recent history of inadequate correction. The reputation of this copy seems to have been acquired from a misplaced trust in its source, perhaps Origen or some other bishop. This lapse in judgment led to several manuscripts like Sinaiticus and Vaticanus being produced with an inferior text of Mark.

This same copy was also probably the source of the missing ending of Mark, which had likely lost its last page.

It is somewhat ironic that many textual critics imagine that the Alexandrian text of Mark is a relatively older and purer form of the text, when it appears to have suffered most of its damage in the latest era of its peculiar textual transmission history. This text apparently originated sometime in the early 3rd century, when MSS were being copied in narrower columns. As far as accidental omissions of significant parts of the text, the Aleph/B text of Mark is probably the worst surviving text known.

Luke has also suffered serious damage in the Alexandrian stream of transmission, but being a much larger book, this damage is perhaps less on a percentage basis, than that suffered by Mark.

mr.scrivener