True story: I was questioned by nice church lady the other day, about why Textual Criticism was important. So I explained the idea of the textual history of the Bible, the discovery of ancient manuscripts, the careful collating of readings in critical editions, the basis of English translations, etc. I told her the basis for the many terse footnotes and brackets, found in modern Bibles.

Her response: "Oh, I never bother with the footnotes. I know they are nonsense. Just read them yourself, you can see they are garbage." She went on to explain that Christians don't really pay attention to scholars, because they know they are wolves in cheap clothing, unbelievers, and mere critics.

I won't say I was floored. But the extent of this 'intuitive knowledge' and instant invalidation of all things text-critical is actually quite sweeping inside live, vibrant churches. Ordinary Christians just don't give textual critics any credibility whatever. The Bible simply has more authority than academia. And this is true in spite of most Bishops, Priests, pastors and church officials being accredited (and often faithless) academics.

Textual critics and other academics might dismiss this as mere bigotry, or ignorance, or magical thinking. But actually its a stunning example of intuitive grasp of the real crisis in Textual Criticism (Biblical) and many other professions, as we stumble into the 21st century.

It seems that the 'lay-church' has always had little use for academics, and apparently even for church authorities. The grassroots 'church' just carries along, with or without professors, commentators, leaders, simply thriving and nuturing itself ultimately on the text alone.

The Problem in Simple Terms

On the one hand, we have never had better access to manuscripts, data, history, and the process of textual transmission than we do now. And we have never had so much science, tools for analysis, and brain-power than we do today.

On the other hand, never has this 'science' of Textual Criticism been more confused about the 'original text' of the Bible. In fact, its even uncertain of any kind of scientific procedure for how to proceed to discover it. And doubt has extended in a sweeping manner not only to whether original texts can even be discovered, but whether they ever existed at all.

And never in the history of Biblical Criticism has the entire field of Biblical studies had less prestige and less scientific credibility than now. The sad part is they've earned this lack of credibility in spades.

The Sad History of Textual Criticism

This will be a unique but terse explanation of what went wrong and why.

1400s - With the invention of printing, and unprecedented opportunities for literacy, people turned away from the previously necessary task of hand-copying texts, to establishing a uniform, universal printed Bible, at least for each language. Two tasks were immediately recognized: (a) the establishment of the original text, (b) the translating of it into the main languages.

At the same time, the political climate created by the previous Crusades, the Inquisition, and the Reformation brought out the problems and complexities of the growth of scientific and free thought against dogmatism and abuse of authority.

1500s - It also became apparent that establishing the original text would not be as simple as thought. Errors and inaccuracies had crept into copies and needed to be spotted and removed. This became a more and more unwieldy task, as more copies (and variants) came to light. Early work of Erasmus, John Mill, Beza, etc., resulted in the establishment of a consensus text, the Traditional or Received Text for the New Testament, while for the Old Testament the Hebrew was used by Protestants, largely bypassing the Latin Vulgate.

But a method for the selection process for readings had yet to be developed.

This was of great concern because the Bible was used as an authority for the correction of the political abuse of power, and was an effective tool in the Reformation of the Christian Churches.

1600s - The Bible, and the default Received Text became the cultural property of every nation who received it, that is, most of Western Europe, and the Protestant countries. It provided a common ground and mind-set for interpreting the world. It was used as an authority to appeal to, and argue and reason about differences in religious interpretation.

1700 - 1900s - Growing uncertainty in regard to the Bible text, (mainly from collation of textual variants), diminished the overall authority of the Bible for many, just as science began to develop and grow as an apparent alternative to religious dogma. Unfortunately, a reliable and convincing method for establishing the Bible text was still very slow in developing. At the same time, the problem of collating the many hand-copies had grown beyond the abilities of one person to manage. The last two great collators of manuscripts were Tregelles and Tischendorf, but 19th century "methods" of Textual Criticism were largely eclectic and coloured by scepticism about Catholic tradition.

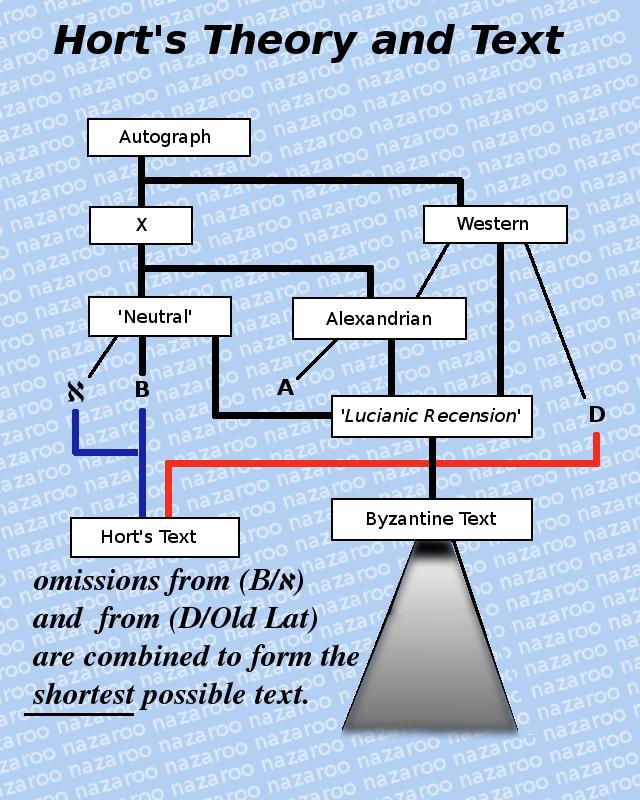

By the late 1800s, scepticism as an early part of 'scientific attitude' and scepticism of historical claims in particular had led to a de facto approach of constructing a minimalist text based on rejecting any variants that might be possible additions or accumulative editing. From Wetstein's original doubt (1752), to Lachmann's deletion program (1831), to Tischendorf's flip-flopping (1869) and finally Hort's stubborn scepticism (1882), ratified by Nestle (1904) and promoted by Metzger, and only slightly modified by Aland (1960), we arrived at the 'standard critical text' of the UBS series, used for most 20th century 'modern' English translations.

But when all was said and done, no credible scientific Text-critical method had actually been developed. Only a stoic scepticism inspired by 19th century materialist science and anti-Catholicism had saturated the field with a minimalist approach, entrenched by simply upholding the status quo for nearly 100 more years.

As the smoke cleared in the late 20th century, from the battles between traditionalists and moderns, we ended up with essentially two NT texts;

(1) The Received Text, essentially the one used by Christians for the most recent 1,000 years, and

(2) The Critical Text, essentially the smallest text that could be constructed, by rejecting any longer variants and accepting as original every significant omission found in the more ancient copies.

Part 2 will examine how it happened that no significant progress in textual-critical methodology was achieved, and why the text bifurcated and remains in two branches today, with loyal apologists for both sides.